The NHS 10-year plan: an overdue opportunity to deliver personalised care plans

In a recent article, we argued that a dominant theme in patient’s contemporary experiences of care is waiting – and that interventions should focus on enabling people to self manage their conditions, and their impact on the way they live, whilst they wait. This blog is the final in a four-part series discussing how the health service could provide a new ‘offer’ of support for self management.

When people experience long waits for their healthcare, their risk of anxiety, confusion, and depression is worsened by the uncertainty of waiting and being unaware of where they can find additional support.

In this series of blogs, we have argued the need to provide people who are waiting with peer support and education for their self management. Both these low cost interventions help people to build the knowledge, skills, and confidence needed to manage their health successfully – and to reduce the number of times they feel compelled to call on urgent and emergency care. However, these benefits are undermined unless people also feel they have an agreed care plan that makes clear who is doing what to support and improve their health.

Of course, health professionals seek to provide as much certainty as possible, and will provide patients with information about their likely prognoses and the immediate next steps in their care and treatment. But the ‘management’ or ‘treatment plan’ is often something the patient only partially understands, and does not control, leaving the feeling of dependence and uncertainty undiminished.

Personalised care planning

For over two decades – starting with the National Service Framework for Diabetes in 2001 – there has been a growing push for a different approach to care planning. Most recently, this has been labelled as ‘Personalised Care and Support Planning’ (PCSP). Instead of starting with a disease and its treatment, personalised care plans start with the person and their priorities. Essentially, the approach aims to ask patients ‘what matters to you?’ – rather than ‘what’s the matter with you?’.

The process of PCSP involves the person in a rounded review of their personal situation, assets, needs, values, and priorities, covering not just biological and physical but also psychological and social domains. It maps not just a person’s challenges and health issues but also their strengths and capabilities and how to build on these. It helps set individualised goals that reflect the person’s own preferences and aspirations, and identifies the actions, interventions, and continuing support required to achieve these.

For the growing numbers of people with multiple conditions, who use a range of services and support, tailored plans like these are the cornerstone of coordinated care. Lord Darzi, in his recent NHS review, states that without co-produced shared care plans, alongside population insights and multidisciplinary teams, “integrated care is not happening” (p75)1.

Implementation and progress

Unfortunately, progress has been slow. The ‘Our Health, Our Care, Our Say’ white paper in 2006 committed that “by 2010 we would expect everyone with a long-term condition to be offered a care plan” (p115): Lord Darzi’s ‘Next Stage Review’ in 2008 emphasised that these care plans should be personalised and regularly reviewed (p41). The 2019 NHS Long Term Plan and its accompanying ‘Universal Personalised Care’ paper made a range of further pledges around personalised care plans for pregnancy; for people with cancer; and people at the end of life – as well as promising metrics, a dashboard, and a national impact statement that have not yet been produced2.

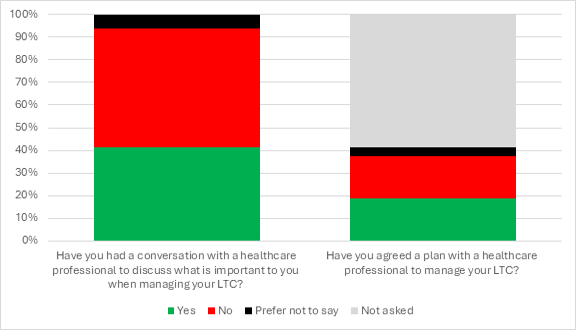

Figure 1 – General Practice Patient Survey data on management of long term conditions (2024)

Source: General Practice Patient Survey, 2024. Base: all patients who reported that they had a long-term condition or illness.

It’s difficult to know how much progress has been made because there is no single service location, template or reporting system for PCSP. Variations in how providers describe and implement care planning and the production of care plans make effective measurement of their prevalence challenging. Perhaps the best data on this subject comes from the General Practice Patient Survey (GPPS): as of 2024, this indicates that only 41.5% of people with a long term condition reported being asked what is important to them when managing their conditions or illnesses and less than 19% had “agreed a plan with a healthcare professional to manage their conditions or illnesses”. But of that 19% almost all – 94% – found the plan helpful.

This was in a context where, as waiting lists rocketed, the percentage of people with long term conditions who did not feel confident managing issues arising from their condition rose from 16.1% in 2018 to 22.6% in 2023. The percentage who said they did not have enough support from local services or organisations rose from 20.6% to 34.9% in the same period3.

Primary and community care is the most appropriate setting for people to engage in PCSP and was seen as the ‘key delivery mechanism’ in the Long Term Plan; but it is only in this year’s Directed Enhanced Service (DES) contract that PCSP has begun to appear, in the form of ‘enhanced care plans’ for people identified as frail. There is a long way still to go.

What’s next: conclusions

This mainstreaming of peer support in mental health services has been facilitated by government policy to expand and improve these services. A similar push is now required to develop peer support for all long term conditions, working in partnership with relevant user groups and charities and learning from those who have pioneered the principles and models.

The new government should put a renewed national drive behind personalised care as part of its commitment to expanding care in the community and prevention, particularly as these interventions help people with long term conditions prevent the development of further conditions and complications.

If Lord Darzi is to be heeded, and patient experience, prevention and primary care are to be prioritised, then the contract and funding for primary care should drive forward an expansion of personalised care and support planning for everyone who can benefit over the next three years. This must be accompanied by Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) commissioning a full programme of education for self management and peer support.

Development of a new ten-year forward plan for the NHS is a crucial opportunity to reimagine the health and care system in a way that recognises patients as whole people – addressing and improving their wider lives, and the lives of our communities, rather than focusing narrowly on episodes of care. Whilst waiting lists will, unfortunately, remain a feature of care for years to come, there are evidence-based, cost-effective methods to mitigate against their consequences, to improve people’s experiences, and to offer a more person centred approach to care.