How to measure patient satisfaction (in five steps or less)

It’s difficult to measure something as subjective as patient satisfaction – but it’s widely recognised that patient experience is a core component of health service quality. If we are to manage patient experience well, we need to measure the things we can and monitor and account for those things that we can’t.

Step 1 – Do you need to measure?

Measurement is necessary when processes or outcomes need to be quantified (eg “are we meeting our targets?”); when things need to be compared (eg “do patients from different groups have equal experiences?”); or, when performance or results need to be tracked (eg “are quality improvement measures improving people’s care?”).

Measuring gives us a before and after allowing us to understand how well something is working. It is a necessary component of a healthcare system striving for person centred care, as it allows us to see through the patients’ eyes (Gerteis et al 1993 [1]) and changes our view from a clinical to patient perspective.

Step 2 – Measure what matters

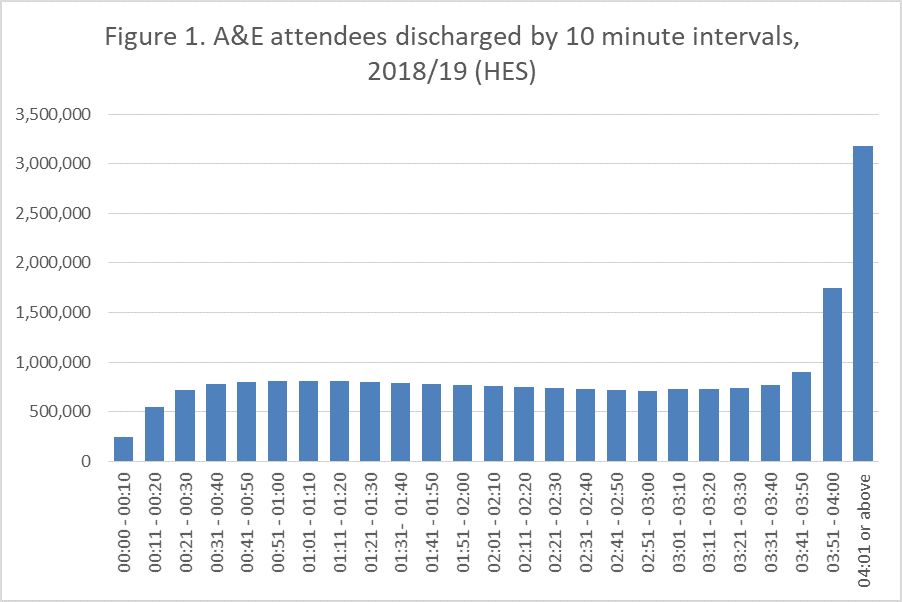

Whilst, it can be helpful to have targets in place to ensure improvements are being seen, they can be counter-productive. A good example is the high-profile four-hour waiting time for A&E units in England. The pledge in the NHS constitution is that at least 95% of patients attending A&E should be admitted to hospital, transferred to another provider, or discharged within four hours.

Figure 1. shows there is a sharp rise in discharges from hospital just before the four hours is reached. This rise is a reflection of staff quickly processing patients to meet the target; it doesn’t give us any indication of the quality of care the patient has received.

At Picker, we use our Principles of Person Centred Care to outline the things that matter most to people. We believe that to deliver high-quality healthcare all eight principles need to be placed at the heart of healthcare provision.

These principles are more difficult to measure than an arbitrary four-hour waiting time. They require high-quality surveys delivered in an unbiased and reproducible way.

Step 3 – Use high-quality methods and valid questions

Surveys are the primary methodology for measuring patient satisfaction – but to avoid bias, they need:

- a representative sample – not just certain types of patients;

- replicable methods – same format, timing, etc for all respondents;

- careful wording – avoid leading and double-barrelled questions; and

- testing – to ensure respondents understand questions consistently.

We use focus groups and interviews with service users to determine the content of surveys, and cognitive testing to make sure questions can be understood. Statistical methods are then applied to detect where respondents may be finding it difficult to answer or where questions are not providing the answers people want to give.

Step 4 – Don’t ask about satisfaction

Experience and satisfaction aren’t the same thing, and there are a number of important shortcomings to asking about satisfaction. This is because satisfaction:

- “implies only that expectations have been met” [2];

- is highly subjective;

- represents “a complex function of expectations that may vary greatly among patients” [3];

- is generally not actionable; and

- “tends to endorse the status quo” [4].

Experiences, by contrast, can be more objective: we can ask people to report about whether or not specific events occurred during their care and treatment. A positive experience is both related to clinical effectiveness and an end in its own right.

Step 5 – Repeat and track results over time

Being able to robustly track trends is a crucial benefit of measurement. Trend data can be used to identify unexpected dips in performance; test the effectiveness of interventions; or contextualise results. However, when using trends, be aware that real changes can emerge slowly and avoid impulsive reactions to individual results.

Without looking at trends, it’s hard to contextualise survey results. Long-term data will highlight critical things such as dips in performance and where interventions have been used, enabling you to assess if they have been effective. Short term point-to-point changes can be affected by random variation and lead to decisions based on anomalies.

Improvements to user experience are best seen as a long-term strategic goal. Trying to achieve changes that will be reflected in the next iteration of a survey is often unrealistic. It’s far better to start improvement work as it’s required and allow time for the trends in the data to change.

So, where do we start with improving patient satisfaction? Firstly, decide if measurement is really what is needed. Then, work out what measures matter most and use high-quality methods and valid questions to get the information you need. Remain focused on people’s experiences by asking about specific reportable events. Once you have completed all this repeat (if needed) at an appropriate frequency and track changes over time.

For further advice or assistance with measuring, understanding, and improving people’s experiences of care, please get in touch with the team at Picker – we’d be happy to help.

References

[1] Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, Delbanco TL eds (1993). Through the patient’s eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centred care. San Franscisco: Jossey-Bass.

[2] Cleary, P.D. (1998). Satisfaction may not suffice! A commentary on ‘a Patient’s Perspective’. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 14 (1) 35-37.

[3] Cleary, P. D. (1999). The increasing importance of patient surveys. BMJ, 319(7212), 720–721.

[4] Williams, B. (1994). Patient satisfaction: A valid concept? Social Science & Medicine, 38(4), 509–516. http://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)90247-X